|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

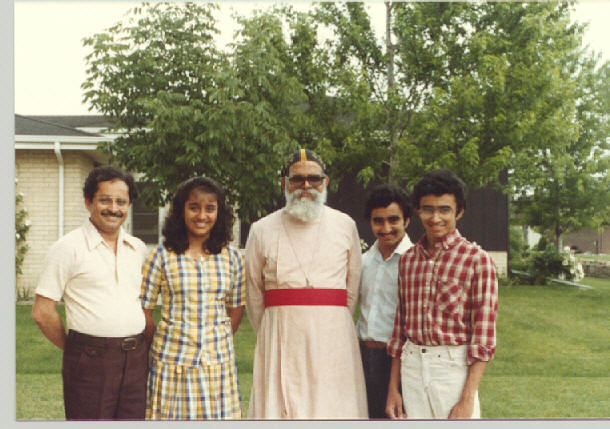

| Oak Park (Chicago), Illinois | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

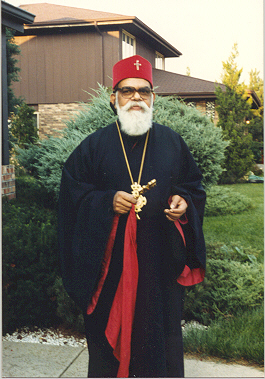

Metropolitan Dr.

Paulose Mar Gregorios

Several memories about Thirumeni flashed through my mind as I entered the Delhi Orthodox Center that day; the images of his erudite lectures, powerful orations, philosophical discourses, spiritual leadership, reflections on his vision for a just and peaceful world, enlightening sermons, and above all, his fatherly affection. I remembered, in particular, his recent leadership of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. A towering figure in the Ecumenical and inter-religious movements, Dr. Paulos Mar Gregorios was the torchbearer chosen to inaugurate its Centenary celebrations, a colorful and grand function held in Rockefeller Chapel at the University of Chicago. Unlike his Indian predecessor of the last century, the Vivekananda of the twentieth century did not have to wait till the end to command the attention of the Parliament! Gregorios Thirumeni was the Archbishop of Delhi of the Malankara Orthodox Church of India and the Principal of the Orthodox Theological Seminary in Kottayam, Kerala. But he was much larger than those official chairs he held in his Church. A leading Theologian of the Orthodox Churches of the World, as well as a former Associate General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, and later one of its presidents, he was well known in mainstream Churches all over the world. However, I did not go to Delhi to meet with the Theologian, the Philosopher, the Metropolitan, the Author, and the socio-political leader. I went there to be with the human being, also known to the outside world as Metropolitan Paulos Mar Gregorios, my life-long teacher and friend, who had showered unconditional love, acceptance, and respect onto my family and myself, much more than we ever deserved. I was ushered into his bedroom as soon as I got there. Thirumeni was sitting on his chair, wearing the plain white kammeeze of the Orthodox Christian priest. A walking stick, which he had been using for a while, leaned against the arm of the chair. I knew he was ill, but he did not look sick. The usual exuberance and energy was not there, but his face looked bright and serene, and his mind was as sharp as ever. I perched quietly on a modest wooden chair, one of two guest chairs in that small, austere room. “How was your flight? I am sorry I could not send my car to the airport to pick you up. I don’t have a chauffeur now.” His hospitality had always been embarrassingly perfect ever since I first met him in 1955. I was deeply humbled once when he waited for an hour at the airport to meet me. “And how is Chinnamma?” He inquired as well about my children Joe, Kurian, and Liz with the love and yearning of a grandfather. He wanted to know about their marriages, their work and educational endeavors. It was he who had first placed his hand on their heads to bless them when they arrived on this planet. Although he was working in Geneva as the Associate General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, he was in Trivandrum for a conference soon after Joe and Kurian were born, and called on us. We felt it was a blessed coincidence. I don’t remember which part of the globe he was trotting when Liz was born. But he paid a surprise visit to bless her too. When Joe was going through a stressful freshman year in college, Thirumeni made a special trip to Champaign, Illinois to see him. When Liz got married, he came over to Chicago from India, bound to a wheelchair, to be the chief celebrant of her wedding ceremonies. She wanted only her Appan (her grandfather, also a priest) or Thirumeni to conduct her wedding. Appan was no more. So Thirumeni had no choice! He was a grandfather-ideal to all of them. Gregorios Thirumeni had played with my children for hours whenever he had a chance to visit with us. He enjoyed playing with all children and would keep on, oblivious to anything or anyone around, whether in a tense and crowded airport in Tokyo, or during a politically charged get-together at an American parish of the Malankara Orthodox Church. He used to say that playing with little children was his only form of relaxation. One of his greatest joys was visiting with the children of the Orphanage in Thalacode, Kerala. The orphanage was one of Thirumeni’s favorite projects and he developed it into a viable institution. In his will Thirumeni bequeathed a significant portion of his estate to this orphanage. Those innocent children always remember him as a loving grandfather. Dr. Gregorios turned into a child when he was with children, and a philosopher, scientist, or king when in the company of the elite ones. I am afraid it was difficult for him to be anywhere in between! He could relate easily with the international roster of his friends like the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa, Dr. Robert Runcie (Archbishop of Canterbury), Pope John Paul I, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Baba Virza Singhji Maharaj (Delhi), Swami Chidanand Saraswathi (Rishikesh), Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Miyan (Luckno), Swami Lokeswarananda (Ramakrishna Mission), Dr. Karan Singh, President R. Venkatraman, and President Roman Herzog of Germany. He could find immense joy in conversing and playing with children as well. Family dinners, when he stayed with us, were always memorable and relaxing. One evening he started explaining Hegel’s dialectical philosophy to Joe, Kurian and Liz who were only in high school! “What is going on here?” I wondered. At the time he had been reading Hegel in original German in order to write a book on the works of the Holy Spirit. He had borrowed the books from the University of Chicago library to read them in our house. Thirumeni explained Hegel’s theories in an understandable, simple, and beautiful way to the children. He told me that he could be sure that he understood those theories only if he was able to make the children understand them. In conversation and lectures, his skills in elucidating even the most complex theological, philosophical or scientific theories were brilliant and unmatched. I am sure he would have had a much larger readership if he had dictated his book the way he was talking to an audience rather than written them by hand in philosophical diction. At another dinner, Kurian asked Thirumeni how he came to know the Emperor Hailie Sellassie of Ethiopia. My children were at an age when kings and clowns filled their fantasy world. They got plenty of stories during the next two hours to enrich them for the rest of their lives! His anecdotal style was an effective way to transmit eternal values to the children. Every story had a sublime aim beyond that of a benign biographical exposition. For a brief article on Thirumeni this may be a rather long narration on his stay in Ethiopia, but for various reasons it is important to include his relationship with the Emperor as it reveals a great deal about the strong personalities of both of these historical figures. The powerful experiences Thirumeni had in Ethiopia tested his faith and values and were important to his spiritual growth and his vision for the world. Long ago, he had told me about an unusual experience he had during the earliest days of his life in Ethiopia where he fell a victim to a torturous and menacing form of small pox. Since no one would visit him or even take food to him for fear of contagion, he was in a sort of solitary confinement in his room experiencing pain, loneliness, and agony. He cried and yelled at God in anger and frustration as most of us do in times of crisis. In that moment of anguish and darkness he heard a distinct voice saying, “Yes my son, my suffering on the cross was worse.” This was a turning point in his life, the end of self-pity and the beginning of a new path, a commitment to follow Jesus. Gregorios Thirumeni, who was then a teacher in Ethiopia by the name of Paul Verghese, had directed the Shakespearean play Julius Caesar for his school’s anniversary celebrations. (A bishop in the Orthodox Church receives a new name when he is ordained as bishop.) In the play he acted as Mark Antony, a role in which Thirumeni’s oratorical talents found full expression. The Emperor Hailie Sellassie was in the audience to demonstrate his special interest in the educational activities of his country. Deeply moved by the performance of ‘Mark Antony,’ the Emperor wanted to meet with him personally. During the conversation Paul Verghese talked to the Emperor in Amharik, the Emperor’s native language. Amazed at this foreign teacher’s command of Amharik, Hailie Sellassie asked how long Paul had been in Ehiopia. “ An year and a few months, your Majesty.” Hailie Sellassie was fascinated by the play and asked for a copy of Julius Caesar to read that night. A few weeks later Paul Verghese received an order appointing him as the Senior Teacher of the Amharik language in the most prestigious High school in Addis Ababa. Soon the Emperor began to invite him to the palace just to listen to Paul speak Amharik. Thirumeni had a remarkable ability to master several languages and had “dabbled in a dozen or more” languages. He wrote a grammar book for the Amharik language during his tenure as a teacher in Ethiopia. He was also proficient in English and Malayalam, his native language. He could handle Hindi, German, French, Sanskrit, Tamil, Greek, Russian, Aramaic, and even a Native American language. Paul Verghese wanted to study theology and got a scholarship to go to Goshen College, Indiana for his undergraduate degree. Hailie Sellassie came to know about this. “You do not need to study any theology. You know enough now. You stay here and work with me. We need you in the Palace,” the Emperor told him. Unsure that he could dissuade Paul Verghese from leaving Ethiopia, Hailie Sellassie asked the Crown Prince, the Archbishop, and a few others to follow up on this issue. But all their efforts were of no avail. Hailie Sellassi was angry and did not communicate with Paul for a while. After all, he, the Emperor, was the ‘King of kings.’ Paul Verghese took his undergraduate degree in two years, and then went to Princeton to study theology. There he completed the requirements for Bachelor of Divinity in two years and he wanted to leave America for India. Love overcomes hurt pride. Hailie Sellassie followed the whereabouts of his favorite “son” and kept track of him. When the Emperor was on a State visit to the United States, Princeton University held a reception in his honor. To the dismay of the president of the university, the visiting Head of State made a special request that a particular graduate student named Paul Verghese be invited to the official banquet. The father meets the son with love, with a heart filled with forgiveness! “So this is your University. We (the Imperial We) have tracked you down. And we know that you have finished your studies and will be getting your degree in a few days. You are coming back with us to Ethiopia. No more excuses,” said the Emperor. There was no one in the palace Hailie Sellassie could trust. Too many enemies from within and lingering threats of coup d’etat! An eternal human dilemma! Return to plough the father’s farm or follow one’s own vision? They were both stubborn people, and pursued relentlessly whatever they wanted from life. Neither one gave in, yet each kept affection and high regard for each other. Paul Verghese went to Alwaye, India to teach Bible at Union Christian College. I was a sophomore there at the time. Religious activities began to flourish with his arrival at the college. Over and above the routine Scripture lessons in the college curriculum, I attended his weekly Bible Study group in the evenings. Weekends were filled with spiritual activities. As President of the Student Christian Fellowship and Secretary of the Philosophy Association, I worked very closely with him for several hours every week. He became my guru and a big brother too. He never turned me down. When he and I were planning an entertainment program to raise funds for the Student Christian Fellowship, he searched through his bookshelf and pulled out Shakespeare’s works. “Why not we produce Julius Caesar?” he mused. Julius Caesar! A Shakespearean Play! In Alwaye College! He must be kidding, I thought. A reassuring smile! Then he told me the story of his ‘acting career’ in Ethiopia. “This is great! Would you play Mark Antony again?” I asked. This was an audacious request by a student to a teacher those days. Professors were kept on a high pedestal and they never acted in a play side by side with students. We never even mingled with the faculty socially. To my surprise he nodded “Yes.” Then who will play the other roles? “Let us ask Joseph Achen to act as Julius Caesar. And, let us try to get George Zachariah for Brutus,” he said. Professor George Zachariah was my Psychology professor. Rev. Dr.K.C. Joseph (Joseph Achen) was a senior faculty member, Professor of English, and a priest too! I did not have the nerve to ask either of them to act in a play. Respectable and serious minded people in India would seldom want to identify himself as an actor. So Paul Verghese took up the responsibility of persuading these men to play those roles. The entertainment went very well, the best one in memory. Everyone welcomed the participation of the faculty and the new, lively interaction between students and faculty. When Emperor Hailie Sellassie paid a State visit to India in 1957 he persuaded the Nehru Government to request Paul Verghese’s services for Ethiopia. When Paul Verghese declined that offer the Emperor sent a direct telegram asking him to meet with the Ethiopian Ambassador in New Delhi. Hailie Sellassie wasn’t going to take “No” for an answer. I was at the Fellowship House, the residence of Paul Verghese, when he received the telegram from the Emperor. The mailman had taken eight hours to deliver the telegram, an unusually long delay even by Indian standards. I told him he should complain to the Postmaster. But, with a smile he said, “You know, I worked as a telegraph clerk in the Post Office for six years before I went to Ethiopia. I don’t want to get a mailman in trouble.” The Ambassador’s mission failed, but the Emperor would not give up. When Hailie Sellassie reached Kerala during his tour he had a meeting with His Holiness Baselius Geevarghese II, the Head of the Malankara Orthodox Church. Paul Verghese was there as the interpreter for H.H. Baselius Geevarghese II, the only human being Paul Verghese would obey without question. The Emperor made his request to His Holiness, who tactfully persuaded Paul Verghese to accept Hailie Sellassie’s request. Soon he moved to the Imperial Palace in Addis Ababa as the Emperor’s Private Secretary and the Minister in charge of Education and Liaison Affairs with India. Life in the Palace could be a dream for common folks like me. But Paul Verghese was not happy there, and was very uncomfortable with the intrigues, power politics, and corruption that went on around the place. It was not the life he wanted, and he wanted to get out of that trap. On a day of State Celebrations, quite unexpectedly, the Emperor called Paul Verghese to his presence. When he went in, the Emperor was sitting on his throne, dressed in his formal attire. The Emperor’s pet lion kept him company, regally watching his master, the ‘Lion of Judah.’ “What do you want to be in life?” asked the Emperor. Carefully observing all the formalities of addressing the Emperor, Paul Verghese voiced his wish, “I want to serve the people.” “ Years from now I will probably be forgotten. But I have a charity fund, The Hailie Sellassie Charity Fund for which I want to be remembered by posterity. You be in charge of that fund.” With awe in the presence of the Emperor, the demure Paul muttered, “I want to serve the people of my Church in India.” Reaching for the power of powerlessness! Suddenly, the Emperor stood up in anger and roared, “You were born in India by mistake. You are an Ethiopian, and I am your Emperor. You obey my orders.” Court dismissed! A week later Paul Verghese received a memo giving him charge of the Hailie Sellassie Charity Fund. He was also personally given shares of the Emperor’s private business endeavors, the Addis Ababa Transportation Company, and the Ethiopian brewing company. The Emperor’s granddaughter, a British-educated, beautiful young woman, was also appointed as Paul Verghese’s secretary. With a twinkle in his eyes Hailie Sellassie later asked Paul Verghese, “How is the new secretary working out?” What is the agenda here! The Emperor wanted Paul Verghese to be his grandson-in-law. “My son is not my son,” the Emperor once told Paul Verghese. Hailie Sellassie did not hold the Crown Prince in high regard. They never got along well. Money started to flow into Paul Verghese’s bank account from the transportation and the brewery companies. Power and money, and now an invitation to be a member of the royal family - the great ‘Temptations!’ Wouldn’t it be unsettling to anyone? But the question is “Was this God’s calling for Paul Verghese.” The favorite son Paul waited. When the Emperor went abroad on a State visit Paul Verghese flew to Yugoslavia and sent a telegram to the Emperor, “ I have left Ethiopia.” The determination to be what he wanted to be! To be true to one’s own spirit! As I write this, in the same dining room in which Thirumeni told the story of the Monarch and the Monk, I can see in my mind’s eyes the look on my children’s faces. Their eyes and ears were glued to Thirumeni, like a Norman Rockwell painting. Thirumeni told them several other stories of his long relationship with Emperor Hailie Sellassie. Some may be worth repeating here, for what they reveal of Thirumeni and echo in his own life. Once, he told them, when Ethiopia was threatened with army revolts the Emperor called Paul Verghese to the Palace for consultation. It was a tense moment. The palace courtyard was filled with the army in rebellion. Hailie Sellassie decided to face them and address them from his balcony. He wore his formal royal attire and was pacing up and down his chamber. Paul Verghese was in the adjoining room along with the Crown Prince, Defense Minister, and all the other Cabinet ministers. No one knew what was going to happen next! Apprehension! Doom! The Emperor called Paul Verghese into his chamber. “I am going to face the Army,” said Hailie Sellassie in a calm, firm voice. Then he grabbed Paul’s hand and said, “Examine my body. I could be dead by a soldier’s bullet in thirty minutes. I want you to be my witness that I don’t have any bulletproof vest on. I have never feared anyone but God!” An embodiment of Imperial courage! The faith of the Head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church! Emperor Hailie Sellassie addressed the soldiers for thirty minutes. They dispersed in peace! As Thirumeni continued his story, I wanted to tape-record his unique eyewitness account of history, but I was afraid that might interrupt his train of thought. Besides, it felt awkward to record a private family dinner chat and make all of us self-conscious. The story continued, and he talked about the coup d’etat. The Emperor was abroad, and the Crown Prince announced over the radio that Hailie Sellassie had been dethroned and that the Prince had taken over as Head of State. Hailie Sellassie flew back to Addis Ababa. The people and a large section of the military rallied behind him. He was back on the Throne again, a second time in his life. The first time Mussolini had dethroned him, but this time his own son had done the deed! He was rattled quite a bit. He wanted to talk this over with Paul Verghese, his trusted counselor. Paul Verghese flew to Addis Ababa and met the Emperor in his private room. Hailie Sellassie asked the guards to close the doors, and that they be left alone. Hailie Selassie poured out his heart. “ You always tell me that I don’t trust people. How could I? It was my own Palace Guards who did this to me,” bemoaned the Emperor. It had been four hours by the time they let the doors of the chamber open. The Crown Prince had his side of the story. He invited Paul Verghese to his palace for dinner. As soon as he was received at the door the Prince signaled that there be no discussions, no chats on the political situation. Every room was bugged by the secret police, the Prince had suspected. After dinner the Prince told the guards, “Two chairs,” and pointed towards the garden in the backyard. He wanted it to be just the two of them, where it possibly was safe to talk. The Prince explained the situation to Paul Verghese and said he was innocent. The military junta had forced him into the radio station, and at gunpoint made him read the statement overthrowing the Hailie Sellassie regime. The Crown Prince said that Ethiopia had changed, and that when he came to power he would allow democracy a chance. The Military Court ruled that the leaders of the coup be publicly executed. That was the law of the land. Paul Verghese voiced a word of protest to the Emperor. “You don’t know anything about Statecraft,” the Monarch shot back at the Monk. When the turmoil subsided Paul Verghese sat down with Hailie Sellassie and gave some suggestions for a future course. ‘Ethiopia and the world are changing. People want to have a voice in running their country. You may have to give the responsibility of day- to-day administration to the people and the Cabinet, and then sit back as a figurehead, like Gandhiji.’ The Emperor called a Cabinet meeting and solemnly proclaimed, “From now on you have the responsibility of running the Government. I shall stay in the background as a figurehead. Whatever good you do, you get the credit, and whatever mistakes you commit, you take the blame for it.” Things went smoothly for a few weeks. Everyone felt relieved and comfortable. But Hailie Sellassie couldn’t help it. On every little issue, the Emperor started calling up the Cabinet ministers to yell at them, “Why did you do this, why did you do that,” and so on. Finally the Cabinet members gave up on ‘democracy,’ and Ethiopia was back to its one-man rule. Hailie Sellassie was too old and too stubborn to change. But the average Ethiopian loved him, adored him, and one sect of people even believed that Hailie Sellassie was their prophet. Hailie Sellassie repeatedly told them that he was only an ordinary human being, but they wouldn’t accept it. They insisted that the prophecy specifically said that the prophet would deny that he was the prophet. Everything about Hailie Sellassis’s life fit the story of their Prophet. A group of such ‘believers’ rebelled against their government in an island state. They said that the Governor of that state had no authority over them; only Hailie Sellassie was their god-king. The Emperor sent Paul Verghese to this island state to tell them that Hailie Sellassie wanted them to know that the Emperor was not a prophet, as they had believed. After they heard the emissary, their Chief held an orange and a knife in his hands, chopped off the top of the orange, and threatened the messenger that his head could be chopped off just like that for bringing this ‘heresy!’ No, the Truth never appeals to blind fanatics! However, Paul Verghese wasn’t intimidated. He persisted and negotiated an end to the rebellion against the governor. Intimidation never worked with Thirumeni. He would always fight against a threat and would never consider running away from it in cowardice. I remember once when a priest in the American parish mentioned to him that Thirumeni had enemies in America, and that his life could be in danger, Thirumeni snapped back, “I will go anywhere I want to. God will protect me”. Fear was an emotion absolutely alien to him. Restlessness and rebellion continued to brew in Ethiopia. General Mangitsu led the military in rebellion against the weakening government of the Emperor. Thirumeni said that Henry Kissinger had assured the Emperor that His Majesty’s life would be safe. Trusting the United States’ promise Hailie Sellassie surrendered and lived as a prisoner in his own Palace. Thirumeni was allowed to visit Hailie Sellassie in the Palace, the last foreign visitor to see him. Hailie Sellassie acted as though he was still in charge as the Emperor. He called his secretary, gave her orders, dictated letters, and so on. She was only Mangitsu’s spy! The Prisoner Hailie Sellassie sat on the chair of the Emperor Hailie Sellassie, and talked to Thirumeni, still with the dignity His Majesty was used to. At the end Thirumeni asked, “After all this, Your Majesty, do you still believe in God?” Hailie Sellassie could not hold on to his facade anymore. He burst into tears and said, “That is all I have left now.” Face to face with the Ultimate Truth! A few days later the Ethiopian Government made the official announcement that Emperor Hailie Sellassie died in his sleep. With tears brimming in his eyes, Thirumeni said, “They poisoned him!” (Years later it was found out that that they had choked him to death with a pillow.) Thirumeni looked distraught. He couldn’t continue his story. As we sat there stunned, he stood up and staggered away to his room. I have seen him in tears only one other time. After suffering from a heart attack, I was placed in the intensive care unit in Edward Hospital, Naperville. He came into my room, sat quietly near me, and with tears in his eyes said, “I never thought I would see you this way.” Let us go back now to the Delhi Orthodox Center where he lived. Thirumeni had gone through several personal traumas during his life including his mother’s nervous breakdown, his own stroke, post-surgical complications, and cancer. But self-pity was not one of his flaws, even though now, here he was with ‘all of the above’ plus fatigue, diabetes, and hypertension. “He walked around with regal dignity, but lived like a Yogi, and he was comfortable at both,” said his biographer Professor K.M.Tharakan. The place of his abode could not have been simpler. His bedroom had only one window. The stone wall that snuggled around the massive Orthodox Center rudely interrupted his view to the outside world. It was no ‘room with a view.’ He had raised the money, and had designed and built the Orthodox Center. From among all the spacious rooms in that multi-storied edifice he had chosen this room, so like the austere, wood-paneled bedroom of Peter the Great in Peterhof, that ornate, opulent Russian Palace in St. Petersburg! An old chair, with two pieces of hard wood on both sides to support his arms, found its place close to the wall. It was kept slightly elevated, propped up on a bunch of unrefined bricks so that he could get up by his own stubborn self with no outside human help. A small, traditional Indian cot found its humble place on the right side of the chair. Underneath was a piece of old carpet with patches of bald spots and diminishing luster. A thin cotton mattress and a pillow clad in white cotton fabric apologetically adorned the bed, awkwardly reminding him that it felt awfully rejected much of the time. A thin, brown wool shawl, neatly folded, lay unobtrusively at one end of the bed. Squeezed between his chair and the bed was a night stand which held a tape player that purred his ever-favorite Gregorian chants, a telephone, a traveling alarm clock, a few books, a pen and an appointment book. The two wooden chairs in the corner of the room didn’t look very inviting to anyone who might think of settling down to exchange small talk. And on the opposite wall, a bookshelf with glass doors held a few books, some odd items of personal interest, and small gifts received. Two beautiful Russian Orthodox icons, the only ornament in this sparse room, adorned the walls, one of Jesus and the other of St. Mary, holding the infant Jesus. Two small silver dhoopakkutties (incense burners) adorned both sides of these icons like worshiping angels. I felt as though they were transmitting the vibrations of a celestial aura over us. Thirumeni took a few Russian and Byzantine icons with him wherever he traveled. Those were permanent fixtures of his personal surroundings, as much as the Masanipsa and the cross on his person. I gave Thirumeni a couple of tapes of Gregorian Chants that I had bought for him. This kind of devotional music usually kept him company when he was alone in his room in Delhi, as well as in hotel rooms, or houses, during his frequent transcontinental travels. A few years ago, when he had stayed with us he gave me the tape of a Gregorian chant of the Christmas-Mass. I immediately loved it and soon developed an enduring taste for it. Did he have a chance to listen to the new tapes I had bought him? I hope he did. But I would never know! I asked about his medical condition. His doctor was planning to start the second course of chemotherapy that week. I knew that he was an avowed apostle of holistic health. I talked to him about my recent presentation at the Midwest Conference of the Biofeedback Society in Chicago on “Stress, Depression, and Cancer.” He reflected for a moment and in a pensive tone said, “If stress has anything to do with my cancer, it is the stress from my efforts to resolve the conflict in the Church.” In the past we had talked about his anguish over the prolonged legal battles between the Patriarch and the Catholicos factions in the Malankara Orthodox Church. He was a Metropolitan in the Catholicos faction of the Church, but his heart and mind were above a narrow vision, and the divisive and petulant squabbles among the two factions. Most people on the Patriarch’s side believed in Thirumeni’s fairness and his earnest desire for a dignified and peaceful settlement. However some extremists on both sides worked hard to sabotage the peace initiatives, and even went to the extent of throwing insults in his face. It was agonizing, and yet he continued his peace mission, as no one else had a better chance to accomplish his noble goals. When he talked to me he sounded hopeless. Although the Patriarch had initially offered to cooperate with Thirumeni unconditionally, Thirumeni was afraid that the Patriarch was being swayed lately by the pressures from extremists on his side of the aisle. This only helped the extremists on the Catholicos’ side to strengthen their antagonism against the Patriarch. Thirumeni was by no means personally accusing the Patriarch. In fact their personal friendship went way back when they had worked together in the World Council of Churches. But lately Thirumeni had lost his line of communication with him and asked me if I knew of anyone whom the Patriarch would listen to. He must have been very desperate, I thought. The Patriarch used to listen to Babu (Dr. Babu Paul, IAS), but now Babu is sort of ‘excommunicated’ from his circle, said Thirumeni. His face turned melancholic and disillusioned. The late Vattasseril Thirumeni, the leader of the Catholicos faction, had passed away in despair and disillusionment. Manalil Achen (Father Yakob Manalil), his secretary to the end, once told me that the failure of Vattasseril Thirumeni’s earnest efforts to work out a peaceful settlement with the Patriarch faction was the main cause of his illness and death. Professor K.C.Chacko, “the black saint of India,” as Viceroy Lord Irwin once described him, also died under similar circumstances, within days after his peace efforts were thwarted. Was this Church under the spell of a curse? I wondered. Thirumeni’s legs appeared to be hurting. He had constant discomfort in his lower legs. I noticed that there were several dark spots on his feet, scars from diabetic sores. He was sicker than he appeared, I thought. I sat down at his feet and tried to massage them. And I found myself embarrassingly inept at it. I can never forget those feet. Gregorios Thirumeni taught me the only kind of exercise I still practice. We used to go for long walks in the late afternoons when I was a student at the Aluva College. He was Paul Verghese Sir then, new addition to the faculty and college community, recent graduate of Princeton University and a brilliant teacher and lecturer of the Bible and philosophy. Wearing white khadar juba and mundu we walked at a brisk, steady pace with arms swinging very lively, as our minds kept busy with philosophy and religion. This is the best form of exercise, he told me. We walked, and we talked, like Socrates and his disciple. I am annoyed with myself whenever I think of my inept, clumsy performance of the ‘massage therapy.’ I could not even do such a simple service for him. I can never go back for a second chance. Death has a grim finality to it. Every moment in life may be the last chance you ever have. Yet the thought that he might die so soon never crossed my mind. I had plans to return after a few months with a video camera and conduct a few interviews with him about his life and philosophy, and his visions for the future. I did not even take a still picture of him this time. Why should I? I was going to come back to spend a long vacation with him! And he was going to be there for a long, long time! Everyone wants to go to heaven, but no one wants to die. All of us will pass through the gate of death some day, but most of us are afraid to think about it. From my clinical practice, and from my own experience, I have come to think that freedom from the fear of death liberates us from crippling existential anxiety. It is important to be at peace with one’s own transition to the other Life. As Morrie Schwartz puts it in Tuesdays with Morrie, “When you learn to die, you learn to live.” As I visited Thirumeni, Cardinal Bernadin’s body was being laid to rest in Chicago. I had a copy of the Chicago Tribune with pictures and an extensive write-up about his life, his struggle with cancer, and his peace and friendship with death. I took the paper along for reading on the plane, and also maybe to share it with Thirumeni. Cardinal Bernadin was an old friend of his, since the days when the Cardinal was Father Bernadin. But I was nervous about bringing up this topic. I did not want to evoke images of cancer-related death before him, but on the other hand, I wanted to make sure that he had already reached this very special peace, a must for everyone of his age and of ill health. Was Thirumeni at peace with the extinction of his own mortal being? When I watched his defiant struggle against his physical disability, his unceasing striving to learn, think, and write, his incessant campaign for a just and peaceful world, I wondered if he would soon detach himself from all these worldly preoccupations. Maybe he had a different way of dealing with life. ‘God gave me this precious life, and I must use every drop of it to my last breath, for His glory.’ Like a burning pellet of camphor at the altar of a deity, did he want to burn it all before God with not a trace left? With a quiver in my heart, I finally told him about the Cardinal’s death. There was a moment of silence, and a wave of gloom rolled over his face. “How old was he? Seventy five?” “No, he was in his late sixties,” I said. Was Thirumeni reflecting on his own life span? I wondered. As I came to read his Last Will later, I realized that my concern about his preparedness to leave this world was unfounded. A week after he suffered a stroke, and with his left hand paralyzed, he wrote from his hospital bed in Room 341 of Krankenhaus Sankt Josef in Germany: “God has been good to me and has begun to heal me miraculously. He could have done it all at once, if He wanted to. He tells me that my faith is not strong enough for such immediate recovery. But He is healing me miraculously fast… I have come to know afresh both how fragile one’s hold upon ordinary biological life is, and also how unshakable is the foundation of the new life which God bestows by His grace. Death is no terror. Even the prospect of being a permanent (that is, till the end of this biological life) invalid holds no terror for me, if that is what God wills. Whatever happens, He can turn it into the good.” I inquired about Avarachen (Paul Abraham of Canada), his baby brother, of whom Thirumeni was most fond, and who was a good friend of mine. Avarachen had come from Vancouver to be with him. “He went to Kerala to attend Yakob’s son’s wedding. I couldn’t go,” he said with a tinge of disappointment. (Yakob was Thirumeni’s brother.) Fate has its own freakish designs. Thirumeni’s body reached his childhood family church in Tripunithura, the same church where the wedding was to be conducted, and the same day it was scheduled to take place, but in a sad way, for the traditional last farewell. In the Malayalam language, the word Veli has a dual meaning, wedding and death. That day was to be the celebration of his Veli, the end of one life and the beginning of another. Thirumeni was showing signs of fatigue. “Have you brought anything to read? There may be books of interest to you in my library,” he said. “Do you have any plans to visit places or other friends in Delhi? I don’t have a chauffeur. But I could find some friends who would take you around." “I have no other plans, Thirumeni. I came only to spend some time with you,” I said. He reached for his walking stick and struggled to get up from his chair as I watched, keeping my impulse to assist him under firm control. I was not at all comfortable watching him struggle though. “I like to do this by myself,” he said, as he dragged his body toward the bed. “My legs don’t seem to have the strength to carry the weight of my body.” I knew his stoic self resented sympathetic helpers. I ventured to help only when he asked for it. A nurse attended him during the day. His physical capacities had been breaking down one after the other over the past forty months, despite his valiant fight against at every stage. I joined the resident priest Father Solomon, and some aspiring priests who lived at the Center, for noon and evening prayers in the Chapel. We then ate Ashram-type meals in the dining hall. I surprised myself by waking up for the prabhatha namaskaram (early Morning Prayer). I can count on my fingers the number of days I might have seen the sun rise in my entire life. My father used to wake me up at 5:00 a.m. for prayer. I couldn’t stand it. I used to fall asleep in the middle of that ritual or I would fake sleep when it didn’t happen naturally. Finally, he gave up on me and carried on with his discipline all his life. But this time it felt different. I had a reason to pray. I joined the worship services three times every day to lift up Thirumeni’s name before God Thirumeni was living on a frugal diet of only fruits and vegetables for over a week at the recommendation of a certain European quack. Father Solomon was of the opinion that this was the reason Thirumeni became too weak at the time. He recalled that Thirumeni had enough energy to teach a two-hour class for the philosophy students from the Jawarhal Nehru University just a week earlier. He had been to Chennai (Madras) only five days ago to address a meeting at the invitation of his friend Mr. Mammen Mappilai of the Madras Rubber Factory. Thirumeni had several complaints about the culinary art of the resident chef at the Center. Sometimes he would say to me “maybe it is my appetite, or a problem with my taste buds.” In his frustration, he had written to us a while ago, “I can’t even get a Vada”, his favorite delicacy. I spent most of my time reading and meditating in the reception-room area close to his bedroom.

Wednesday, November 20, 1996 In spite of his inadequate skills in handling Thirmeni’s frustrations, his attendant Thomas cared about him very much and did the best he could. Forgive me for inserting this paradoxical lamentation of Thomas in this somber chronicle. When Thirumeni passed away, the grief-stricken Thomas wailed in tears, with a profound sense of loss, “Ente Deivame! Enne vazhakku parayaan ini aarum illallo!” (“Oh, God! I have no one left to scold me!”) I have heard some people say that Thirumeni was difficult to work for. His perfectionist, hard-working, and idealistic personality had no room for stupidity, inefficiency, and corruption. I once asked him, “ Would they be working as orderlies if they had been as bright and smart as you are?” Many people went to work for Thirumeni with a hidden agenda, such as his finding a job for them in the Gulf or securing admission and scholarship in an American University. They believed that Thirumeni could easily do this for them if he wanted to. It was true that Thirumeni was reticent about asking for personal favors from foreign countries. Living in America for thirty years, I knew that these things were also beyond his reach. But people in India have trouble understanding this, as many of these things are obtained through personal recommendations in India. They left him and resented him for his failure to live up to their unrealistic expectations. It would be a tremendous frustration to anyone to be bombarded with unceasing demands and expectations, especially when he did not have the resources to meet those needs. It was even more distressing when those petitioners would not believe that he had his own limitations. Cerebral and friendly as Thirumeni was much of the time, volcanic anger shot through his rigid veneer of rationality and composure without much warning. In Psychoanalytic terms, his Superego was so domineering that the Id forces staged a ruthless revolt, playing havoc, destroying everything on their path like a tornado. Or in Jungian terms, a pussycat at the Conscious level can be a tiger at the Unconscious level. He was painfully aware of this ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ contradiction in him, but he never managed to integrate those opposing forces successfully. In his autobiography, Love’s Freedom – The Grand Mystery Thirumeni writes about his young adulthood: “There was quite a bit of goodness in me, but I knew that a lot of sheer wickedness was lurking underneath all the time. Ambition could not always be distinguished from love of domination and power, from the desire for adulation and flattery. Yearning for love and affection often took the form of seeking glory and honor…I loved to be praised, but I was afraid to be loved, mainly for fear that I could not take it when the love would be withdrawn. I was once the object of great love and affection from my mother, but its apparent withdrawal as a result of her illness was a trauma that I never got over. My personality was unmistakably dual and unintegrated.” Unfortunately, the stroke he suffered exacerbated his problems with his irritability. Brain damage of the right hemisphere, as he had suffered, might have resulted in impairment of emotional control and change of personality. Within a week after he suffered the stroke, my wife and I talked with him over the phone. We talked at length and felt that his verbal abilities and thought processes were intact. Those capacities were very important for the way he lived his mission in life. The impairment of emotional control was expected, considering the nature of his stroke. Despite his impairment, and his reputation for such angry outbursts, I have never witnessed any such incidents myself, nor has anyone in my family. His reactions were not as idyllic as his pre-stroke years, but somehow he managed to keep them within acceptable limits. He has always treated us with love, understanding, kindness, and respect. He was a man of several paradoxes. Although he benefited a great deal from his education at Princeton, Yale, and Oxford, he had serious reservations about Indians settling down in Western countries and being engulfed by the seductive Western life-styles and values. When I was leaving for America for post-doctoral training, he appeared at our house, as he always had whenever I had gone through a crisis or a major change in my life. “Northwestern is a good University, but do not settle down in America. You must come back,” he said in a stern voice. But then he seemed to accept my ventures. “I have a few dollars left over from my last trip to America. You might need some money on your way.” These are the things he loved to hate in the socioeconomic order of the century: the monstrosities of industrial and defense establishments, the secularism and materialism of the European Enlightenment, and the cultural imperialism and neo-colonialism of the West. He attacked these things with a passion wherever he got a chance. Thirumeni’s friend Dr. Cherian Eapen (Moscow), a former Social activist and trade union leader says: “Thirumeni taught the people of India that they should learn from the Enlightenment liberalism, imperialist pragmatism, and socialist humanism” while avoiding the down-side of these philosophies. He thought, said Cherian, that India should learn from “Western Europe, the United States, and the Socialist countries, but with a critical mind. India should have an identity of her own, independent of these three, but in collaboration and interaction with them, and should at the same time develop self-respect for her own traditions, philosophy, and the arts.” Thirumeni’s fight for social justice was not limited to India. He had worked with Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement in America. He led a delegation of churchmen from the World Council of Churches to meet with several government leaders of the world, pleading for economic sanctions against the racist South African government. In a follow-up correspondence after his meetings with James Baker, the US Secretary of State and Senator Edward Kennedy, the Senator sent him a picture of Thirumeni’s team visiting with the Senator and wrote, “To Metropolitan Gregorios, with deep admiration for your tireless struggle for freedom in South Africa.” Thirumeni envisioned a society that held robust Christian social values, rooted in faith in God, love, and altruism, devoid of selfishness and monitory motives. When he found that profiteers and oppressors dominated even ecclesiastical establishments, he turned to the leftist revolutionary movement, only to be disillusioned even more deeply. He refused to take into account human psychology and the pragmatic problems it would entail to maintain the kind of utopian society he had envisioned. For most people self-interest, not spiritual authenticity, is the core motive that propels their lives. Humanity has not, it seems to me, developed much beyond the narcissistic stage. Agape, compassion, and altruism are still elements of a noble dream. Nevertheless, he continued to cling to his vision to the very end. In 1995 he wrote, “Alas, the communists became as dogmatic, corrupt and power hungry as the Roman Catholic Church and dug their own graves. But I still remain committed to socialism as the nearest alternative to the just society I am envisaging as a Christian.” It was a sedate post-breakfast hour. I went to his room to see how he was doing. “Nebu just called,” he told me. “They are coming to see me on the 18th of January.” He seemed happy about it. Nebu and Betty (Drs. Abraham and Betty Koshy) had been close to him for several years. In their home in Michigan, away from all the maddening crowds and demanding roles, he would shed all his official masks, and relax as a genial old man. Many people in Kerala do not know that he loved to be treated as an ordinary human being, but bishops are seldom treated that way in India. The expectations of people for him to be a certain way, according to their own preconceived notion of how a high priest and an influential leader should appear and act put tremendous pressure on him, as it would on any authentic human being. In our homes we reached beyond his official, public persona and connected with the true human being within him. He was relaxed and pleasant when people would allow him to be genuine, and loved him for what he was. “Pinne kaanam,” (“See you later”) he had told Nebu. The pinne never came to be. Dr. Cherian Eapen had told me of his plans to visit Thirumeni on December 9th. But, alas, he too was deeply disappointed. Thirumeni had an earlier appointment with his Master, and that must be kept. Two women disciples came to see him around the late afternoon on Wednesday. They were Hindu Brahmins and professors at the Jawaharlal Nehru University. As it turned out, they were determined to feed him that evening. They brought dosa mix, masala, and Sambar and made masala dosa on the stove in the adjoining cubicle. I knew Dr. Jayashree and her father from the World Congress of Spiritual Concord held at the Vanaprasth Ashram, in Rishikesh. She had helped Thirumeni a great deal in organizing that marvelous event, along with Dr. Cherian Eapen. Thirumeni sat up on his chair, a small food tray on wheels placed in front of him. It had just enough space for two dinner plates, one for him and the other for me. I sat on the other side of the portable table. They served steaming masala dosa and sambar, the best I had tasted in a long time. Vestiges of the unscrupulous stroke asserted itself. His left hand was paralyzed, and he struggled to prove that he could take care of things with one hand alone. The dosa kept skating around on his plate as he fumbled to slice it with a fork. I watched this ‘chasing around’ for a little while. He wouldn’t ask for help. Finally I put my fork firmly on his dosa, like holding a live catfish down by its neck, and held it in place. As if nothing had happened he chopped off slices from his dosa, mixed it with sambar and ate. He ate three of those delicious masala dosas with sambar as those daughters of caring kept on sliding fresh dosas on to our plates. As he finished eating, looking very satisfied he said “ I have been looking forward to this for many days.” It was our last meal together, and I believe it was the last of his enjoyable suppers in the company of friends and disciples. A kind of Last Supper! Served by disciples from another Faith! Dr. Jayashree’s friend who came to see Thirumeni said she was originally from Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu. This led Thirumeni to talk about his current research on the ancient Dravidian civilization of Southern India. He told us that South India had active trade relations with China, Europe, and the Middle East. King Solomon’s commercial ships visited this country every two years. A cyclone or some other devastating natural disaster had wiped out its ancient cities, including the city of Kancheepuram. In his characteristically scholarly way he went on giving a treatise on the South Indian culture and civilization. I noticed on his nightstand a rare book on this new research area, one he might have been reading currently. Sai Baba was on the news that day. Thirumeni talked about the kind of miracles Sai Baba was known for, and of an experience he once had with a Yogi who claimed similar powers or sidhis. This particular Yogi once came to Kerala and created gift objects as if from the air, and gave them away to his devotees. One such object was an expensive idampiri conch shell, which had a religious significance for the Hindus. Thirumeni became curious about this sidhi and paid him a surprise visit at his house near Madras. The Yogi appeared to be a very unassuming man, and treated Thirumeni quite deferentially. When Thirumeni asked him about the sidhi, the Yogi poured into Thirumeni’s hand a bunch of moonstones, exactly the same number and kind Thirumeni had on the cross he was wearing at the time. He had never seen Thirumeni or his cross before, and had no advance notice of Thirumeni’s visit. “How did you do this?” asked Thirumeni. The Yogi told him that through his extrasensory perception he saw that Thirumeni was on his way to visit him, and that he had bought those stones from a store in Madras and had kept them in his house. Through the power of his sidhi he transferred the stones into his hands from inside the house where they had been stored. Yogis do not create something from nothingness; they only transfer objects from one place to another with the yogic powers. According to the yogic traditions, he could have transferred those stones directly from the store without the owner’s knowledge. But that would be a theft, and he did not want to do that. Conversion of one form of energy to another and transfer of objects from one place to another are sidhis, which have been documented, Thirumeni said Chandraswamy, the controversial Guru of some politicians and business magnates the world over, was also in the news. Thirumeni recalled his encounter with this ‘godman’ during the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. Chandraswamy had gone to Thirumeni’s room and had tried to befriend him saying, “ We have so much in common, we should work together.” In his characteristic way, Thirumeni shot back, “As far as I know, we have nothing in common, and I am not interested in working with you. You may leave now.” Thirumeni described him as an adept in Tantric yoga, a form of Yoga with several controversial practices and pujas, with only very few adherents among mainstream Yogis today. Pointing to a publisher’s catalogue from his nightstand, he asked Dr.Jayashree if she would order a particular book on Tantric yoga for him. I was amazed that even at this state of his ill health he continued to explore the frontiers of knowledge, doing research, reading, thinking, teaching, and writing. There was no giving up on life and its mission. He was by no means a novice to the Vedic philosophy and wisdom of India. I remember that when Dr. Karan Singh began his speech on Hinduism at the Parliament of the World’s Religions acknowledged Thirumeni who was on the podium as a discussant, and said, “Of course, Father Gregorios knows more about the Vedas than anyone else in this audience.” A royal recognition from a Vedic scholar, prince, diplomat, and politician! We discussed current politics, religion, science, and the philosophy of modern medical sciences. He seemed to be in the pleasantly erudite and entertaining mood that I had seen him in the past during the dinners he had with my family in our home. An hour or two went by, and his voice was beginning to fail. We suggested that he took some rest. He moved over to his bed from his chair, again defying the power of his infirmity. Dr. Jayashree knelt down on her knees, the traditional Hindu way at the feet of the Guru, and Thirumeni placed his hand on her head to bless her. When the women were on their way out, I kissed his hand for blessing, turned off the lights and left the room. I went to my room and, reclining on the bed with my head resting on the cold wall behind, slipped my legs under the rasai (blanket) to get halfway comfortable. I thought of the very few comforts – like the meal prepared for him by the Hindu women – which had graced his last days. I then opened my Bible for my bed time meditation. It read, “On the way to Jerusalem he was passing along between Samaria and Galilee. And as he entered a village, he was met by ten lepers, who stood at a distance and lifted up their voices and said, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.” When he saw them he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went they were cleansed. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice; and he fell on his face at Jesus’ feet, giving him thanks. Now he was a Samaritan. Then said Jesus, “Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine? Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” And he said to him, “Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.” (Luke 17: 11-19)

A silent

moment with God, then I turned off the lamp and went to sleep. Delhi was the same - cold nights, balmy days, dust, dirt, and automobile exhaust fumes. As if these were not sufficient to choke any living thing on earth, maintenance workers kept vigorously scraping with sandpaper the interior walls of the Center all day long to repaint that edifice. Preparing for some important event! I thought. Morning prayers, noon prayers, and evening prayers, and the barely nutritious meals as usual! And Thirumeni in his room, confined as a prisoner of his own body! A professor of genetics at the CMS College, Kottayam and his wife, a scientist, came to see him. They lived near the Sophia Center in Kottayam and were very close to Thirumeni. After spending a few minutes with him they came out visibly upset and in tears to see him debilitated and under-nourished. Thirumeni had asked them to meet me before they left. He had told them, “He looks out for me more than any one else.” As they mentioned this to me, my heart cringed, I felt very, very small inside. I did care about him, but I did not deserve such a special recognition. Was there a dark lining to the silver cloud of his tribute to me? Did he feel neglected by his church and its people for whom he devoted his whole life? Earlier, on October 10, 1996 after a series of grueling experiences at hospitals, and disheartening struggles to regain health, he faxed us a three-page letter describing his ordeals. “…I wrote all that to make you understand that my worry was not about the Lymphoma, but about the fact that nobody close to me was looking after me. It was only through the help of my Hindu friends and disciples that I was finally able to get treated at AIIMS – nobody in my Church or family, or the centre would do it. Now my brother is here, my nephew the neurosurgeon Sojan left only two days ago. Lots of people gave me money, and I have enough;” It may not be politically correct for me to write this. But it was his feeling, at a time when he was deeply frustrated and lonely. How can we not understand it? Let the chips fall where they belong. Dr. Sojan Ipe called from Kolenchery, Kerala. After a brief conversation Thirumeni told Sojan that I was with him and then handed the phone over to me. He stayed with Thirumeni and took care of him in Delhi during the first series of chemotherapy. The second series would start tomorrow. Cognizant of Thirumeni’s ambivalence toward allopathic treatments, he told me the new series was milder and asked me to persuade him to go through it. I just listened. Some oncologists in America had told me that his type of cancer advanced at a slow pace and that by the time it could gobble him up he would have been gone from something else. Well! For a change, Thirumeni had confidence in a doctor, his oncologist Dr. V. Raina, Professor of Medical Oncology at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Delhi. That was good, I thought. Finally he could work with a doctor without putting up a fight. I remembered the letter he had faxed us about a recent experience at a hospital in Mumbai (Bombay). His close friend and Governor of the State Mr. P.C. Alexander, with whom he had been staying, took him to the hospital as a patient from the Raj Bhavan (Governor’s Mansion). Even with all that clout behind him the experience in Bombay had been a dreadful episode, worse than a nightmare. Hospitals often have an attitude problem. Many of them act as though they are too busy to pay attention to the patient’s sentiments, and they have a culture which makes them blind to anything alien to their customs. Once you check into a hospital, it is as if some malevolent wrecking crew runs over you with a vengeance, demolishing your dignity, privacy, free will, intuition, feelings and what not! Thirumeni would never surrender his free will for anything on earth. He was one of those “difficult patients.” I was preparing to leave the next morning. I went out to the neighboring shopping center to buy some gifts for my family. The entire area was dusty and filthy, and I could not stay out too long. I knew that Thirumeni had a social work project to help the people in that area. As conditions there existed then, it would take a million Thirumenees to raise that neighborhood to the level we are accustomed to in America or even in Kerala. And that was the world in which he chose to live and work. I had to leave at 4:30 in the morning to catch the flight to Thiruvananthapuram. I didn’t want to wake him too early in the morning to bid farewell, so at bedtime I went in to say goodbye to him. He was in bed, reading a book. We had a brief chat. I raised my concerns about finding a good chef to prepare some agreeable food for him. “We tried everything. Asked so many people in Kerala through the church. Announced in all the parishes in Delhi. No one is available,” he said in abject despair and frustration. Domestic workers are difficult to find among Keralites these days. I kissed his hand to receive his blessing. Soon, closing his eyes, he turned onto his right side facing away from me as if he did not want to see me leave. I stepped back, turned off the lights and left the room. Should I leave Delhi now? Or should I stay until his chemotherapy was over? I had second thoughts about leaving. Well, I had already confirmed my flight, and it was difficult to find another one. India has a way of making small things difficult and irksome. Thirumeni! Thank you for sparing me the agony of seeing you die right before my eyes. I felt an ominous sensation as I was leaving the Orthodox Center behind. And a thought flashed through my mind – “This place won’t be the same to me anymore.” Friday, November 22, 1996 My wife called the Orthodox Center and Thirumeni answered the phone. “Baby left this morning. I was happy he came,” Thirumeni said. “Chinnamma eppozha ingottu varunne?” (“Chinnamma, when are you coming over?”). She sensed his yearning to see us all. “No plans for the immediate future, Thirumeni,” she said apologetically. His voice was feeble, and it didn’t sound as robust as it used to. Yet, he wanted to talk. “You sound very tired, Thirumeni. Let’s not talk too long.” That was our last contact with him. Saturday, November 23, 1996 Thirumeni had been steadily gaining more strength since I saw him Tuesday. I read a report that he had even gone up to his study and resumed his writing, putting his companion, the laptop computer to work. Finding a chef for Thirumeni was my immediate preoccupation. My cousin Mr. Iype Thomas, the lay trustee of the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church, offered to send one of his employees, a chef, to Delhi. This chef was a Hindu, a young man from the Nair community, and cooked very good vegetarian meals. Will Thirumeni object to having a Hindu do the cooking for him at the Orthodox Center? “Not at all. He is above all that!” I assured them. But soon Thirumeni would have no need for a chef! Soon he was going to go beyond the world of Vada and Dosa, beyond everything of importance on this planet. Sunday, November 24, 1996 A telephone call woke me before sunrise. “Gregorios Thirumeni kaalam cheythu.” (Passed away). Around 1:00 a.m. Sunday, Thirumeni called his attendant Thomas for a drink of water. He was uncomfortable and an hour later he called Thomas again. This time it was chest pain. And it got worse as minutes passed by. Father Solomon and staff took him to the nearby hospital. But the doctors could not revive his heartbeat. And Thirumeni left his mortal body at 3:30 Sunday morning. I attended the Quorbana at the St. George Church, Trivandrum. The priest gave a eulogy with the usual platitudes. Did he understand Paulos Mar Gregorios? Almost no one in his own Church did. I was no exception either. Next door, at the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church, Dr. Babu Paul eulogized his old Guru in a very touching way. Babu knew Thirumeni, and I knew Thirumeni. Like those blind men who saw the elephant! Thirumeni used to leave personal copies of his books with me when he visited with us in Chicago. He hoped that I would read and comment on them. Occasionally, I gave a critical review of those books, but I really could not grasp their depth and global significance. The day after his Oscar Pfister Award lecture, given at the Annual Convention of the American Psychiatric Association, (he was the first Indian ever to receive that prestigious honor), he and I sat together at my house to listen to a tape recording of his speech. The topic of his presentation was “The Threefold Role of Religion in the Healing of Mind, Body, and Soul.” This was supposed to be an area familiar to me, but I got the essence of his speech only recently, after I had done a lot of reading and work on that field myself. By then he was gone forever and needed no comments from me. I began reading his books again and got only a glimpse of his wisdom and vision. In a review of his book, Enlightenment- East and West, The New York Times wrote that it was one of the ten most important books published in this decade. The reviewer said, “After Vivekananda, this work helps us to get to know the soul of India.” I might need a lifetime of reading and research to understand the mind of this great man. In over 1900 years of its existence, the Orthodox Church of India had never produced another son of his scholarly caliber, and only future generations will fully appreciate his contributions to his Church and the world. In his Last Will this Jnana-Karma-Bhakthi Yogi from Aarsha Bhaarat has this word for us all: “I leave this word to all who survive me: Love God with all your mind and all your will and all your feeling and all your strength. Live for the good of others. Pursue not perishable gold or worldly glory. Wish no one any evil. Bless God in your heart, and bless all his creation. Discipline yourself while still young, to love God and to love his creation, to serve others and not to seek one’s own interest. Pray always that God’s Kingdom may come and all evil be banished from this created order.” (The Last Will) This was what he taught me in Aluva College, India in 1955, and this was what he taught me in 1993 in Rishikesh at the foothills of the Himalayas. Knowing him personally for forty-one years I know that these words came from his heart and he lived them the best way he could. Monday, November 25, 1996 The rest is history, already known to the public through extensive media coverage in India. I watched the long, long funeral procession in Kottayam, a spectator among thousands of the ‘faithful’ children of the Orthodox Syrian Church of India! A Manorama Daily van in the funeral procession paused for me. Someone inside spotted me in the crowd. The staff of the Delhi Orthodox Center was in it, upset and in turmoil. I acknowledged their courtesy, but asked them to move on. I would rather walk. The tears dripping from the darkened clouds in the sky only seemed to complement the mood of the day. I felt very much in tune with it as it enveloped me, and as I moved with the crowd. Mourners of all Faiths and politicians of all ‘colors’ lined up from Kochi to Kottayam. Several miles! A mass of people in profound bereavement! Several priests, deacons, men, women, students, children – they all were there to claim ownership of their famous son of the Church now. “There can’t be a single chef among them!” I mused. Thirumeni’s body reached its final place of rest, the body that encased this free spirit for seventy-four eventful years. Prelates, politicians, cabinet ministers, and Justices were all there to eulogize him. Messages of condolence from his personal friend and President of India Mr. K. R. Narayanan and the President of the Congress Party Mrs. Sonia Gandhi as well as so many others who knew him personally blared over the loud speakers. But the powerful voice that had thrilled and inspired over five thousand delegates from all over the world at the Parliament of the World’s Religions was silent. The echo of the thundering applause and the standing ovation at Chicago were dreadfully mute. The Vivekananda of this century will speak no more. I stood in line, along with the thousands of other mourners, to touch his feet and get a last glimpse of his face. Caught up in the fast-moving crowd, I got a split-second to look at his face. This was not the face I wanted to engrave in my memory. I left right away. Thirumeni was not afraid of the other world. He has a friend over there, - his Lord! With a face lit up in transcendent love and bliss! ******* Copyright © 1998 by Joseph E. Thomas, Ph.DCorrespondence may be addressed to Dr. Joseph E. Thomas, 16W731 89th Place, Hinsdale, IL 60527, USA. E-mail:josefet@aol.com Some comments about this article: “…It is very touching and deserves to be read by Thirumeni’s friends, disciples, and many others.”

Rev. Dr.

K. M. George, Principal, Orthodox Theological Seminary, Kottayam,

Kerala. Dr. Charles Craig Twomby, Washington, USA.

Correspondence may be addressed to Dr. Joseph E. Thomas, 16W731 89th Place, Hinsdale, IL 60521, USA. E-mail: josefthomas@msn.com |

|

|||||||||

|

© Copyright St. Gregorios Orthodox Church,

Oak Park, Illinois

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

It

was Tuesday, November 19, 1996, a chilly fall morning in Delhi. Although

I needed rest after the long flight from Chicago, I had made last-moment

changes in my travel plans and flew straight from Bombay to Delhi. I

couldn’t wait to see Gregorios Thirumeni. (The Malayalam word

Thirumeni is a respectful way of addressing Bishops and high priests

in Kerala, equivalent to Most Reverend). I had listened to

an intuitive nudging when I changed my itinerary, and that gave me the

chance to be with him during some of the last days of his life.

It

was Tuesday, November 19, 1996, a chilly fall morning in Delhi. Although

I needed rest after the long flight from Chicago, I had made last-moment

changes in my travel plans and flew straight from Bombay to Delhi. I

couldn’t wait to see Gregorios Thirumeni. (The Malayalam word

Thirumeni is a respectful way of addressing Bishops and high priests

in Kerala, equivalent to Most Reverend). I had listened to

an intuitive nudging when I changed my itinerary, and that gave me the

chance to be with him during some of the last days of his life.